Author: Richard L. Fricks

Evil and the Divine: Personal Pain, Biblical Spin, and the Universal Dilemma

In this post, we turn to three key sections from Chapter 5 of The Problem of God—“It’s a Personal Question,” “It’s a Biblical Question,” and “Not Just a Christian Problem.” In these pages, Clark shifts from philosophical abstraction to a more emotionally charged defense of God’s silence in the face of evil. He attempts to humanize the problem, spiritualize the pain, and distribute the burden of explanation across all worldviews. As always, let’s begin not with belief, but with curiosity.

1. When Emotion Becomes Strategy

(Responding to “It’s a Personal Question”)

Mark Clark rightly observes that suffering isn’t merely an intellectual puzzle—it’s deeply personal. And in that, he’s correct. When tragedy strikes, it doesn’t matter how many degrees you have in theology or philosophy; the pain is immediate, and the questions are raw.

But here’s where the strategy begins.

By pivoting so quickly to the emotional dimension of suffering, Clark subtly implies that asking why suffering exists is less important than finding comfort in it. He wants us to stop pressing the logic and instead lean into the warm idea that “God suffers with us.”

This move sidesteps the contradiction at the core of Christian theism:

If God is all-powerful and all-loving, why does evil exist at all?

Clark would rather we seek refuge in faith than hold belief accountable to reason. But the very fact that suffering is so personal—so wrenching—makes the absence of divine intervention even harder to excuse. It intensifies the problem. It doesn’t solve it.

Imagine telling a child dying of leukemia that “God is suffering with you.” The child doesn’t need a suffering companion. She needs healing. And if God could provide it but doesn’t, what exactly do we mean when we call Him good?

2. Job: The Bible’s Most Problematic Theodicy

(Responding to “It’s a Biblical Question”)

Clark next turns to the Bible, and specifically to the book of Job, as a meaningful response to suffering. He implies that Job offers the deepest insights into how a believer should understand pain.

Let’s look closely.

The setup of Job is this:

God makes a wager with Satan over Job’s faithfulness, giving Satan permission to destroy Job’s life to test him. Job’s children die. His wealth vanishes. His body is wracked with disease. And all of it is allowed—not stopped—by God.

Is this the “best possible framework” for understanding suffering?

It’s a disturbing one. Job’s suffering isn’t the result of his actions. It’s not justice. It’s not discipline. It’s divine spectacle.

And when Job finally demands an answer, God doesn’t give him one. Instead, He launches into a whirlwind monologue:

“Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth?”

(Job 38:4)

Translation?

“I’m God. You’re not. So don’t question me.”

This is not comfort. This is not clarity. This is a power play. And the resolution—where Job is “rewarded” with more children and wealth—treats human life like replaceable inventory.

If this is the biblical foundation for understanding suffering, it crumbles under moral scrutiny.

3. Universalizing the Problem Doesn’t Solve It

(Responding to “Not Just a Christian Problem”)

Clark’s final rhetorical move in this section is clever: he reminds readers that all worldviews must grapple with suffering, not just Christians. Atheists suffer. Buddhists suffer. Everyone suffers. So Christianity shouldn’t be singled out for criticism.

This is a subtle sleight of hand. Because the real issue isn’t the existence of suffering—it’s the incompatibility of suffering with Christian claims about God.

Let’s be clear:

- If there is no God, suffering is tragic but expected. It’s what we’d predict in a world shaped by random mutation, natural selection, and indifference.

- If there is a God who is all-loving and all-powerful, suffering becomes a contradiction.

You can’t have all three:

- God is all-powerful.

- God is all-loving.

- Evil exists.

Something has to give. And Clark, like many apologists, wants to keep all three—and blame the tension on our limited understanding.

But ignorance is not a solution. And turning suffering into a “universal dilemma” doesn’t resolve the Christian contradiction. It only tries to dilute it.

Conclusion: Truth Doesn’t Need to Comfort to Be True

The problem of evil and suffering is not solved by making it personal, wrapping it in scripture, or spreading the blame. Those may offer emotional relief, but they do not offer logical coherence.

If Christianity’s God exists, then every childhood cancer, every earthquake that buries families alive, every instance of rape or genocide—every one of these happens under His watch, with His knowledge, and according to a plan we are told is good.

That claim demands scrutiny. And no amount of emotional storytelling can make it make sense.

In the end, we’re not asking for comforting answers.

We’re asking for honest ones.

The Illusion of the Soul

The Real Problem of Evil: Not Evidence for God, But Against One

This post is part of our ongoing series responding to The Problem of God by Mark Clark. We’re moving chapter by chapter, examining Clark’s arguments through the lens of evidence, reason, and what we call The God Question—a philosophy that begins not with belief, but with curiosity. Our goal is not to mock or belittle, but to critically and thoughtfully respond to the claims made, helping readers engage with the deeper issues beneath the surface.

🔍 Clark’s Opening Framing: An Appeal to Emotion

Mark Clark begins Chapter 5 by asserting that “this is the most personal chapter in the book.” That immediately tells us that emotion will drive much of the content that follows. And sure enough, it does.

He recounts personal pain—his mother’s cancer and death, his own physical suffering from a degenerative disease, and emotional abuse by his father. These are real, powerful, and humanizing experiences. But Clark attempts to move from the universality of suffering to a very specific conclusion:

Suffering is not evidence against God, but a reason we need Him.

This is the central move of the chapter. And it deserves close examination.

🧠 The Bait-and-Switch of Emotional Authority

Clark’s argument operates like this:

- We all suffer.

- I’ve suffered too.

- So let me tell you what suffering means.

This rhetorical sequence is powerful because it feels honest. But it also risks becoming manipulative. It subtly shuts down the deeper philosophical question—why does suffering exist at all in a universe supposedly governed by a loving, all-powerful God?—by overwhelming the reader with pathos.

The emotional groundwork makes it hard to question the logic without seeming cold or heartless. But we must question it.

❓Is Suffering Really a “Reason We Need God”?

Clark claims that suffering doesn’t negate God’s existence. Instead, it shows our deep need for God. He writes:

“We ask for answers. God doesn’t give us answers. He gives us Himself.”

This is poetic. But it’s also hollow. It assumes that God’s silence in the face of suffering is not a problem, but a feature of divine love. In other words: God doesn’t fix it because His presence is enough.

This, of course, raises a brutal contradiction: If God is powerful and loving, why is His non-intervention framed as an act of compassion?

The better explanation may be far simpler—and far more honest: There is no divine being answering prayers or intervening at all.

🔄 Reframing the Burden of Proof

Clark tries to turn the problem around. He argues that suffering only feels like a problem for the believer—because we expect a good God to do something about it. But for the atheist, he suggests, suffering shouldn’t be a problem at all. It’s just nature playing out—no meaning, no evil, just randomness.

This is a common apologetic move: to claim that atheists “borrow” their moral outrage from Christianity.

But that’s intellectually dishonest.

Non-theistic philosophies—like secular humanism, Buddhism, or Stoicism—have deeply coherent ways of explaining and confronting suffering. These worldviews acknowledge suffering without invoking a morally culpable, invisible deity.

In fact, atheism removes the moral contradiction entirely: in a natural universe, we suffer because of biology, environment, randomness, and human cruelty—not because a benevolent cosmic Father chooses not to intervene.

🔚 Where to Pause for Now

Let’s stop here, just before Clark begins offering the classic Christian responses to suffering (i.e., free will, soul-building theodicies, and Jesus’s suffering as solidarity).

In our next post, we’ll examine those claims in detail.

The True Myth

At The God Question, we critically examine religious truth claims using reason, evidence, and a deep awareness of psychological and cultural conditioning. This ongoing blog series is responding section by section to Mark Clark’s The Problem of God. Clark writes from an evangelical Christian perspective, seeking to answer modern skeptics. We read with both care and scrutiny. In this post, we explore the final portion of Chapter 4, “The Christ Myth,” specifically the concluding section titled The True Myth.

📘 Summary of Clark’s Argument

In this final section, Mark Clark shifts from defensive rebuttal to theological interpretation. He attempts to explain the myth-like structure of Christianity not as a problem—but as its beauty. Drawing on C.S. Lewis’s notion of Christianity as “the true myth,” Clark argues that the Christian story fulfills the deepest longings of humanity found in other myths and belief systems. He quotes Romans 2:14–16 to assert that God has written a moral law on every heart, and he appeals to the inner resonance of the gospel narrative to justify its truth.

In short: myths point to something real. Christianity is the myth that became fact.

🎯 The Core Claim: Myth Doesn’t Undermine Truth—It Reveals It

Clark asks us to consider that mythic parallels between Jesus and earlier pagan gods aren’t evidence that Christianity borrowed or evolved from these stories—but rather, that God “seeded” the world with these myths to prepare the human heart for the gospel. He frames Christianity as the fulfillment of every ancient human story about dying and rising gods, redemption, sacrifice, and divine intervention.

This argument hinges on the assumption that resonance equals reality—that because the story of Jesus feels meaningful and archetypal, it must be grounded in historical fact.

🧠 Critical Response: Resonance Is Not Evidence

From The God Question’s perspective, this is precisely where the shift from thoughtful investigation to theological rationalization occurs.

- Emotional appeal ≠ objective truth. That a story resonates with our longings—our desire for justice, love, sacrifice, and eternal life—does not mean it is historically or metaphysically true. Fairy tales, legends, and Marvel movies also resonate.

- The Lewisian move collapses the line between myth and fact. C.S. Lewis argued that Christianity was a myth that happened to be true. But this is not an argument for its truth; it’s a poetic restatement of belief. It’s beautiful theology, but not persuasive evidence.

- The moral law argument is culturally shallow. Quoting Romans 2 about a “law written on the heart” ignores the enormous diversity of moral systems across cultures and history. Evolutionary psychology and social anthropology offer far better explanations for shared ethics than divine inscription.

🔍 What’s Missing in Clark’s Conclusion?

Clark ends this chapter with what feels good, what sounds grand, and what echoes C.S. Lewis’s literary mysticism. But he does not offer:

- Historical evidence for the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus (that’s postponed to later chapters).

- A rigorous response to the most obvious and natural conclusion of the evidence: Christianity is part of the myth-making human project, not its fulfillment.

- Acknowledgment of non-Christian perspectives—the millions who feel deep emotional resonance in Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, or even atheism.

In essence, Clark offers a grand “what if?” to close the chapter:

“What if nothing could be more natural in the plan of God than the existence of such stories?”

To which we at The God Question respond:

What if the far more natural explanation is that humans make stories that reflect their fears and longings—and Christianity is simply the most dominant version in the Western world?

🪙 Concluding Thought

Clark’s closing argument reveals a critical shift—from evidence to affirmation. It is not a conclusion grounded in history, philosophy, or science. It is a conclusion rooted in faith seeking literary beauty. And while that beauty is powerful, it is not proof.

This is not the problem of God.

It is the problem of wanting something so badly to be true that we mistake the ache for the answer.

Why the JFK–Lincoln Comparison Doesn’t Rescue the Jesus Story

Featured Quote:

“The parallels are uncanny. But no scholar believes that because of these similarities there is any legitimate connection…” — Mark Clark, The Problem of God

The God Question Response:

In Chapter 4 of The Problem of God, Mark Clark attempts to discredit mythic parallels between Jesus and earlier gods by appealing to a popular list of coincidences between Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy. It’s an entertaining section—but deeply misleading.

Yes, there are bizarre similarities between Lincoln and Kennedy: both concerned with civil rights, elected 100 years apart, assassinated on a Friday, and so on. But these parallels are purely trivial and incidental—no one claims JFK was a myth modeled after Lincoln. Both men are verifiably historical. The comparison serves no meaningful purpose other than to entertain or surprise.

When it comes to the Jesus story, however, skeptics aren’t pointing out fun coincidences. They’re noting that long before Christianity emerged, there were religious myths with divine sons, miraculous births, sacrificial deaths, and triumphant resurrections. These motifs weren’t trivia—they were sacred narratives embedded in the cultures that predated Christianity.

Clark’s comparison is what logicians call a false analogy. The Lincoln-JFK parallel doesn’t even belong in the same conversation as Horus or Dionysus. You can’t equate popular historical trivia with deeply rooted religious storytelling.

Here’s the real problem: if a new religion today began telling a story that mirrored the life of Jesus—but with only updated details (say, a carpenter from Idaho born of a virgin who dies and rises three days later)—we’d immediately suspect copycat mythology. That’s precisely what critics argue happened in the other direction with Jesus.

To dismiss this with a wink and a trivia list is to avoid the real question altogether.

So we ask again: Is Christianity an original revelation—or a brilliant remix?

Krishna and the Virgin Birth Parallel

🚩 Mark Clark’s Claim

In The Problem of God, Mark Clark dismisses the oft-cited parallel between Jesus and the Hindu deity Krishna, particularly the claim that Krishna was born of a virgin. He argues:

- Krishna had seven siblings, which in his view, undermines any claim of virginity.

- The miraculous conception story involves a white elephant impregnating his mother, which he says is “spectacular” but “not a virgin conception at all.”

- He concludes that the parallels to Christianity are weak or fabricated, and suggests that some pagan stories actually borrowed from Christianity, not the other way around.

🔍 What Does the Evidence Really Say?

Clark’s rebuttal simplifies or misrepresents Hindu mythology and ignores the nature of myth-making, particularly in oral traditions that evolve over centuries and contain symbolic rather than literal meanings.

Let’s address each of his key points:

1. Krishna’s Birth Story

Krishna’s mother Devaki was the sister of Kamsa, a tyrannical king. Upon hearing a prophecy that her eighth son would kill him, Kamsa imprisoned Devaki and her husband Vasudeva, killing each child as they were born. When Krishna, the eighth child, was born, he was miraculously smuggled out and raised by foster parents.

Was it a virgin birth?

No, not in the literal biological sense. But neither was Jesus’ birth in any historically verifiable sense. The claim that Jesus was born of a virgin appears only in two Gospels (Matthew and Luke), and even those accounts are riddled with literary tropes, anachronisms, and theological motives. The concept of a divine or miraculous conception is common across mythologies and serves as a symbol of divine selection or intervention, not necessarily a gynecological claim.

Further, while Clark points to seven siblings as a refutation, this is biologically irrelevant to the idea of divine intervention in one particular birth. Miraculous conceptions in myth often occur after prior normal births—this does not disqualify the miraculous nature of the latter.

2. The White Elephant Myth

Clark claims that a white elephant impregnated Krishna’s mother. This is actually a confusion with the birth of Siddhartha Gautama (the Buddha), not Krishna. In Buddhist tradition, Queen Maya dreams of a white elephant entering her side, a vision interpreted as foretelling the Buddha’s divine birth.

There is no known Hindu text that describes Krishna’s conception via a white elephant. By confusing these mythologies, Clark undermines his own credibility. Such a conflation would be like attributing Moses parting the Red Sea to Muhammad—a basic factual error.

3. Parallels and Plagiarism

Clark insists that “several of these stories come later than Christianity and borrow from it.” This is a common apologetic tactic, but it is chronologically and academically dubious.

- The Mahabharata, where Krishna’s story appears, is dated centuries before the Common Era.

- Krishna worship was well established in India long before Jesus of Nazareth is believed to have lived.

- The oral traditions and folklore surrounding Krishna go back possibly as early as the 9th century BCE.

Apologists often invoke the idea of pagan stories borrowing from Christianity, but this is historically and geographically implausible when it comes to Indian texts, which predate and developed independently of any Christian influence.

🧠 The God Question’s Core Philosophy

Let’s apply our framework:

| 🔍 Lens | Insight |

|---|---|

| Curiosity over certainty | Rather than defending Christian uniqueness at all costs, we must ask: why do so many cultures tell stories of divine births, miracles, and resurrected saviors? What human need or cultural pattern do these myths reflect? |

| Evidence over belief | Clark demands historical scrutiny for Krishna but suspends that scrutiny when it comes to Jesus. A consistent approach reveals that all divine birth narratives lack empirical evidence and share common mythological features. |

| Seeing faith as human | The Krishna story—like that of Jesus—reflects human hopes, archetypes, and storytelling patterns. The real question is not whether one is “true” and the rest are “false,” but what these stories tell us about us. |

🔚 Conclusion: Dismissing Parallels Doesn’t Prove Christianity

Mark Clark’s treatment of Krishna is riddled with factual errors, cultural misunderstandings, and apologetic bias. The virgin birth parallel may be symbolic, but so is the Christian version when viewed through a historical-critical lens.

Rather than undermining the case against Christianity’s uniqueness, Clark inadvertently reveals how common the themes of divine conception, miraculous life, and divine mission are across world religions—including those predating Christianity.

The more honest approach is not to defend one myth as uniquely historical while labeling all others as “fabricated,” but to recognize that myth-making is universal, and Christianity is one expression of this larger human pattern.

Attis and the Resurrection Parallel

Series: The Problem of God – Chapter 4 Response

Post #5

🔍 Clark’s Claim

Mark Clark argues that skeptics overreach when drawing parallels between Jesus and Attis. He claims that:

- Attis was not born of a virgin.

- Attis was not crucified to redeem the earth.

- Attis’s death involved genital mutilation under a tree, not crucifixion.

- There was no resurrection, only the magical growth of hair and a moving pinky.

- The entire comparison is a stretch used to “fit a preconceived narrative.”

Clark ends with the line: “Call me crazy, but I think it’s safe to say that this is not a parallel with the resurrection of Jesus.”

🧠 A Critical Analysis Using The God Question’s Core Philosophy

1. The Strawman of Literal Equivalence

Clark once again leans heavily on hyper-literal readings of pagan myths to dismiss any parallels. But scholars drawing comparisons aren’t typically claiming identical narratives — they’re tracing thematic and mythological patterns:

- Attis is a dying and “resurrecting” god, tied to seasonal cycles, particularly vegetation gods who “die” in winter and “rise” in spring.

- These motifs are symbolic. No one claims Attis literally rose from a grave in 30 CE Judea. That’s not the point.

- The real question: Why do so many ancient myths include death and return motifs? And why does Christianity mirror those?

Clark refuses to engage with these thematic layers. Instead, he debunks a cartoon version of the myth — a clear misrepresentation of the scholarly argument.

2. Ignoring the Evolution of Religious Stories

Religions borrow. Stories evolve. Attis, like many figures in ancient religions, existed long before Jesus, and his worship included:

- A March festival with ritual mourning and celebration of return.

- Sacred pine trees.

- Bloodletting rites and themes of regeneration.

By the 1st century BCE, Roman cults to Attis included language of rebirth and immortality. That Christianity appeared in the same cultural soup, with similar motifs, is not mere coincidence. It’s cultural osmosis.

To ignore that is to ignore the entire field of comparative mythology.

3. A Question of Selective Skepticism

Clark is skeptical of Attis’s connections to Jesus, yet entirely uncritical of Christianity’s own borrowing. Consider:

- Jesus dies on a “tree” (cross), just like Attis under the pine.

- Jesus’s resurrection is not historically verifiable — like Attis’s.

- Both myths feature blood, sacrifice, symbolic rebirth, and religious ritual.

If we’re to demand literal virginity, exact crucifixion, or precise bodily resurrection as standards for a “valid” parallel, then all mythological comparison collapses — including parallels Christians make with Old Testament “types” and prophecies.

Why accept typology in one direction and reject it in another?

💬 Final Thoughts

Attis is not identical to Jesus — no myth is. But that’s not the point.

The point is that Jesus doesn’t stand alone in history as a dying and rising god. Attis is one of many figures who predate Christianity and feature death-rebirth motifs deeply symbolic in human storytelling.

To argue that Christianity arose in a vacuum — completely uninfluenced by the surrounding mythological environment — is intellectually dishonest.

The story of Jesus, as told by the gospels, fits into a pattern of ancient religious archetypes, not because it’s false because of that, but because it reflects the same human longings, anxieties, and symbolic systems as the rest.

That’s not myth-busting. That’s myth-understanding.

Dionysus: Dismembered Gods and Recycled Myths

This post is part of The God Question, an ongoing response series to Mark Clark’s apologetic book The Problem of God. Each post critically examines a section of the book using reason, evidence, and The God Question’s Core Philosophy: Begin with curiosity, not belief. Today we’re responding to Clark’s section on Dionysus in Chapter 4, “The Problem of the Christ Myth.”

🍷 Who Was Dionysus?

Dionysus was the Greek god of wine, ecstasy, ritual madness, and rebirth. His cult was popular across the ancient world and deeply symbolic—touching on life, death, and transformation.

If you’re looking for echoes of Christian motifs in earlier mythology, Dionysus is an unmistakable candidate. But Clark wants to dismiss all parallels as superficial, weak, or downright false.

Let’s examine the three he targets.

1️⃣ Born of a Virgin? Depends on Your Definition

Clark mocks the claim that Dionysus was born of a virgin. He recounts the myth of Semele, a mortal woman impregnated by Zeus (via lightning), and says, “This is not a virgin birth.”

But that depends on whether you’re looking for biology or mythology.

In many traditions, Dionysus is twice-born—first through Semele, then through his father Zeus, who either swallows his heart or carries him to term. These are not natural births. They are mythic signals that Dionysus is divine, destined, and otherworldly.

Like Jesus, he is set apart from the beginning. That’s the common thread—not whether their mothers had intact hymens.

2️⃣ Born on December 25? So What?

Clark again debunks the claim that Dionysus—or Jesus—was born on December 25. But this is largely a red herring.

Nobody seriously argues Jesus was born in late December. The point is that Christianity adopted a pagan holiday, slapped a new name on it, and made it Christian.

It’s not about who was born when. It’s about how Christianity assimilated earlier religious ideas, imagery, and calendar slots to appeal to Roman audiences already steeped in myth.

3️⃣ Death, Dismemberment, and Resurrection

Here’s the most compelling thread.

Dionysus, in one version of the myth, is torn to pieces by Titans, who eat everything but his heart. Zeus saves the heart and resurrects him—a death-and-rebirth cycle.

Clark scoffs: “A man rising after crucifixion and a god restored from a heart aren’t the same thing.”

Of course they’re not.

But they’re not supposed to be.

These are variations on a universal theme—death and rebirth. It’s what Joseph Campbell called the monomyth, the Hero’s Journey, the dying-and-rising god archetype that spans cultures and centuries.

Christianity didn’t invent this theme.

It just anchored it in time, gave it a name, and called it exclusive.

🧭 Final Thought: Dismissal Isn’t Disproof

Clark’s method here is to dismiss anything that isn’t a carbon copy of the Gospels. But myth doesn’t work that way.

Myth evolves. It flows. It adapts.

Dionysus doesn’t need to be Jesus to make the point. He just needs to show that the idea of divine death and resurrection was already well in circulation long before Christianity made it “history.”

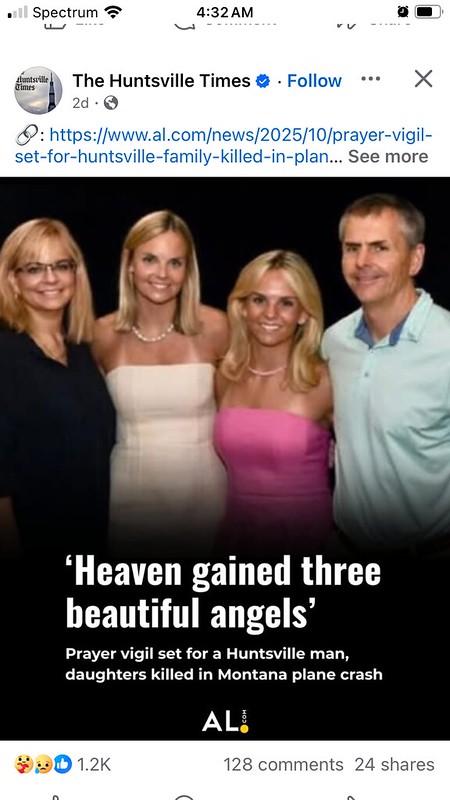

“Heaven Gained Three Angels”: When Journalism Preaches Instead of Reporting

How a Newspaper Headline Became a Sermon—And What That Says About Our Culture

I saw the headline and had to look twice.

“Heaven gained three beautiful angels.”

This wasn’t posted by a church or a grieving relative. It came from The Huntsville Times, a professional media outlet, as it promoted a story from AL.com about a tragic plane crash in Montana that killed a father and his two daughters.

And with that headline, journalism stopped being journalism.

✝️ Not Reporting—Preaching

It’s one thing to quote a grieving mother who says, “They’re with Jesus now.” That’s personal. It’s human. It’s part of the story.

But when the headline declares that heaven gained three angels, the paper isn’t quoting—it’s asserting. It’s adopting a specific theological worldview and presenting it as if it were fact.

Imagine the outcry if a headline had said:

“Three lives lost. No god answered.”

That would be labeled offensive. Cold. Atheistic propaganda.

But when religious language is used—especially Christian language—it somehow slides past our filters. It feels “normal.” It feels “comforting.”

And that’s precisely the problem.

🧠 The Comfort Trap

Why did AL.com choose that headline? Because it comforts. Because it fits the mold. Because it avoids the unbearable reality of what happened:

- A young, vibrant flight instructor died.

- Her sister, still so full of life, died with her.

- Their father, a man who raised and flew with them, died too.

- One woman—their mother—is left behind with a silence no prayer vigil can fill.

Saying they became angels in heaven is not truth. It’s a story we tell because the real story hurts too much. But pain doesn’t justify abandoning truth. And journalism, of all places, should not be where truth goes to die.

🔍 But What’s the Evidence?

Let’s ask the obvious question:

What evidence is there that these three are now angels in heaven?

The answer is none.

No data. No observation. No credible, testable claim. Just inherited beliefs and cultural rituals. Repeated so often that we confuse them for reality.

If we truly care about honoring the dead, we should honor the truth of their lives—not overwrite it with fantasies.

😔 What This Headline Reveals

This headline exposes something deeper about our culture:

- We are terrified of death.

- We’d rather believe in invisible comfort than visible suffering.

- We confuse sentiment with truth—and elevate the former over the latter.

Journalism should not reinforce that confusion. It should challenge it.

Because every time a newspaper becomes a pulpit, the public loses an opportunity to think. To reflect. To face what’s real.

And in a society addicted to soft lies, we need more clarity—not more comforting illusions.

🧾 Final Thought

I don’t know what happens when we die. No one does.

But I do know this: it cheapens our grief when we skip past the sorrow and reach for a heaven we can’t see, a god we can’t prove, and wings that were never there.

If The Huntsville Times wants to share hope, let it do so through human compassion, through truth, and through the incredible life stories of those we’ve lost.

Not through preaching.

Not through platitudes.

And not by pretending.